- Better Society -

- 9mins -

- 1,315 views

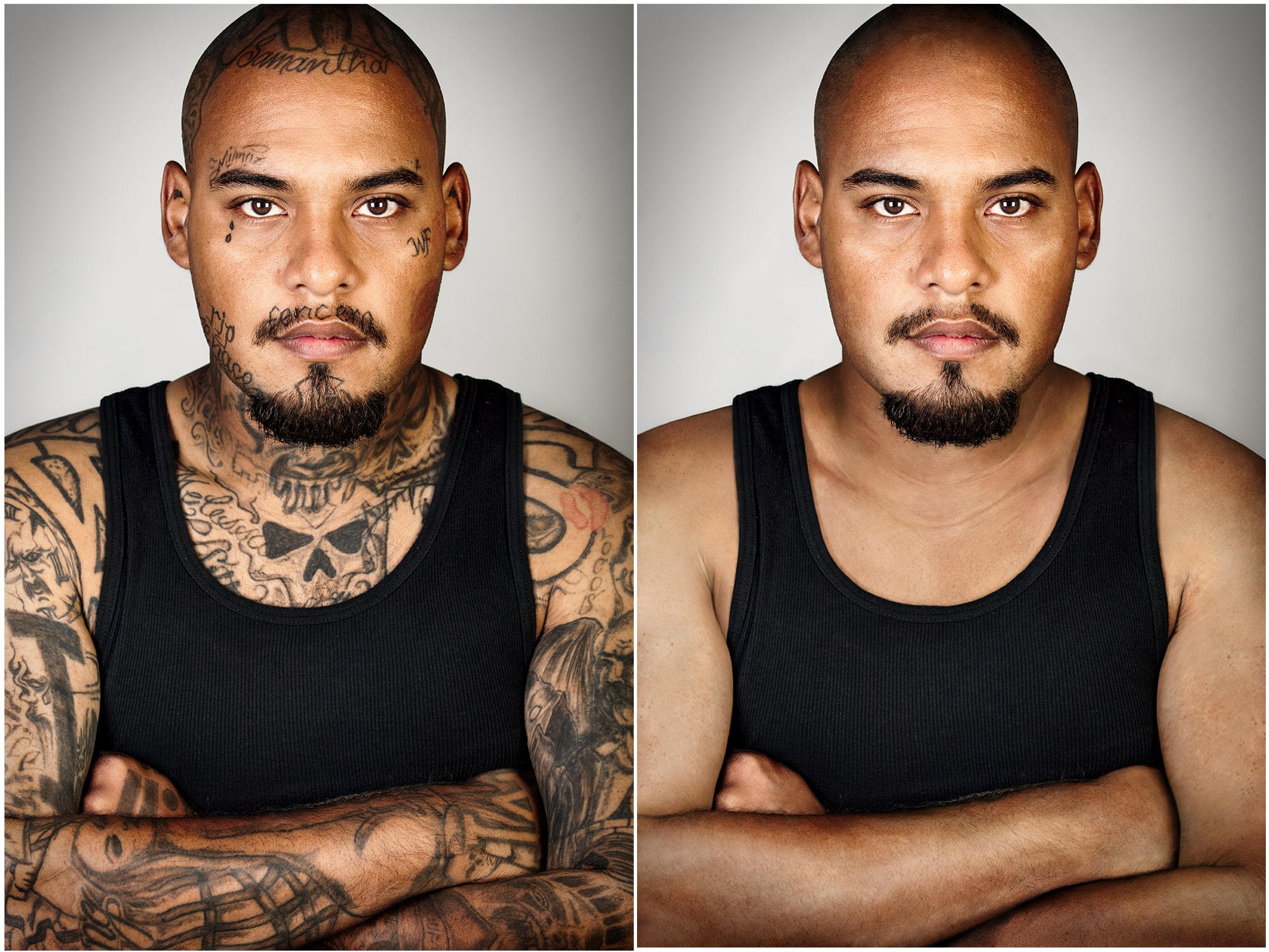

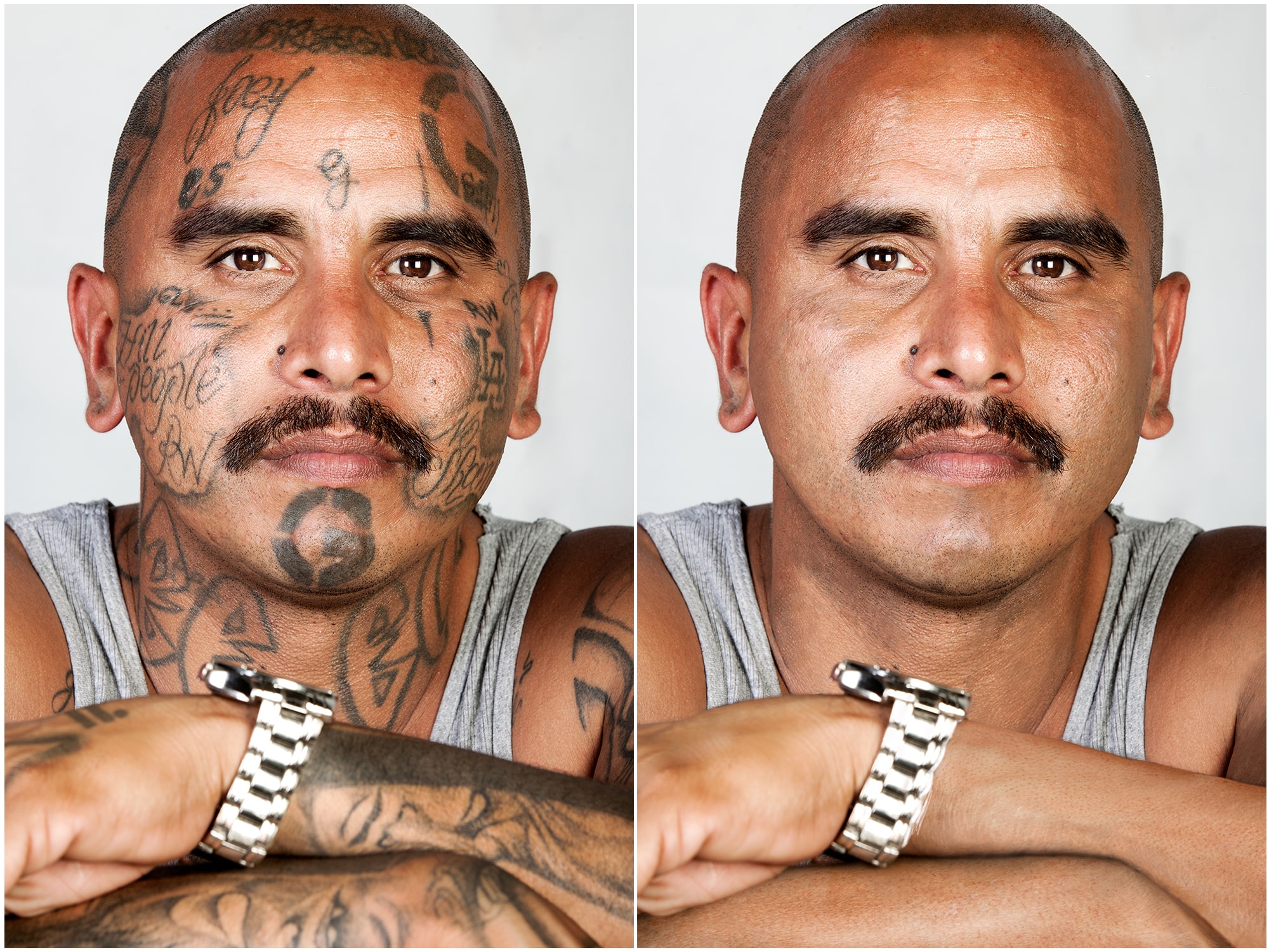

What lies beneath the surface of the Skindeep Project?

The story of the former gang members who got to see themselves without their tattoos, and the Jesuit priest who has dedicated his life to their rehabilitation.

What lies beneath the surface of the Skindeep Project?

Photographer Steven Burton met all his subjects through Homeboy Industries. Homeboy Industries is the largest gang rehabilitation and re-entry program in the world. For over 30 years, Homeboy Industries has stood as a beacon of hope in Los Angeles to provide training and support to formerly gang-involved and previously incarcerated men and women, allowing them to redirect their lives and become contributing members of the community.

Skin Deep, Looking beyond the tattoos

Skin Deep, Looking beyond the tattoos is a portrait series by photographer Steven Burton that seeks to understand the impacts tattoos have on former gang members and people trying to escape the gang life. How we as a society judge ex-gang members with tattoos and ultimately how they judge themselves.

Portraits are taken of the participants. Their tattoos are then digitally removed creating before and after images. The subjects are then interviewed on video while being presented the portraits.

Steven hopes this project helps put a very human face on a group of people that are so often demonised by society. By giving them a forum to talk about themselves, families, aspirations for the future and what tattoos mean to them, while the public is educated about the obstacles these individuals must overcome to re-enter society. To purchase the book please go to ‘Skin Deep, Looking Beyond the Tartoos’, on Amazon, published by Powerhouse books.

Source: StevenBurtonPhotography

What is HomeboyIndustries?

What began in 1988 as a way of improving the lives of former gang members in East Los Angeles has today become a blueprint for over 250 organisations and social enterprises around the world, from Alabama and Idaho, to Guatemala and Scotland. The Global Homeboy Network is a group of like-minded organisations committed to impacting the lives of those in their communities.

Each year Homeboy Industries welcome thousands of people through its doors seeking to transform their lives. Whether joining their 18-month employment and re-entry program or seeking discrete services such as tattoo removal or substance abuse resources, clients are embraced by a community of kinship and offered a variety of free wraparound services to facilitate healing and growth. In addition to serving almost 7,000 members of the immediate Los Angeles community in 2018, their flagship 18-month employment and re-entry program was offered to over 400 men and women.

In 1986, when Homeboy Industries’ founder, Gregory Boyle became pastor of Dolores Mission Church, it was the poorest Catholic parish in Los Angeles. The parish included Aliso Village and Pico Gardens, then the largest public housing projects west of the Mississippi. They also had the highest concentration of gang activity. That was saying something, given Los Angeles’ reputation as the gang capital of the world.

At the time, law enforcement tactics of suppression and criminal justice policies of mass incarceration were the prevailing means to deal with gang violence. But where others only saw criminals, Father Greg saw people in need of help. Today, Homeboy Industries is the largest gang intervention, rehabilitation and re-entry program in the world, welcoming thousands through its doors each year.

Source: HomeboyIndustries

Homeboy is often called on to serve as “parent”

Homeboy provides job training positions and free social services for formerly gang involved and previously incarcerated men and women. Each client is assigned a Case Manager on day one who helps them set a goal plan that may include: obtaining a high school diploma or GED, a course of action for release from parole or probation, and a general game plan for needed services, classes, and skills in order to find outside employment.

Many of the Homeboys and Homegirls arrive into young adulthood with no support system and absent families. When these young men and women teeter in their stability, Homeboy is often called on to serve as “parent.”

On the website, it explains:

‘What we want to provide our clients at Homeboy is a supportive community, a sense of family and a place where they come to help find their strengths, learn job skills, get an education, learn new life skills, and become contributing members to their families and communities.

Life at Homeboy begins for our trainees with work in the maintenance department. During the course of their time at Homeboy, trainees move from maintenance to a vocational skill-building position in one of our six social enterprises, or an administrative position in our program headquarters.

Daily activities for the “homies” (our trainees) might include attending a class such as Computer Basics, Bridge to College, Building Healthy Relationships, Anger Management, or Parenting, and perhaps having a one-on-one appointment with a mental health counselor and a tattoo removal session.

Daily life starts each morning at Homeboy with morning meeting, where every staff member joins to hear the agenda for the day, share successes, and preview upcoming events. This meeting is closed with the “thought of the day,” a small piece of wisdom or inspiration from one of our trainees or staff to help us keep on track for the day.’

Source: HomeboyIndustries

How to find HomeboyIndustries and Steven Burton

Watch their reactions here. Follow Skindeep Project and Steven’s other work on his website and Instagram. Check out HomeboyIndustries on their website and Facebook page.