- Inspiring People -

- 6mins -

- 221 views

How your holiday photos can help researchers track endangered species

A recent study led by researchers from Ohio State University’s (OSU) Imageomics Institute has shown that photos people took and posted on social media during their holidays featuring zebras or whales have an unexpected benefit.

How your holiday photos of zebras and whales can help conservation

Vacation photos of zebras and whales that tourists post on social media may have a benefit they never expected: helping researchers track and gather information on endangered species, writes Jeff Grabmeier, of The Ohio State University. Scientists are using artificial intelligence (AI) to analyse photos of zebras, sharks and other animals to identify and track individuals and offer new insights into their movements, as well as population trends.

imageomics uses AI to extract biological information on animals directly from their photos

"We have millions of images of endangered and threatened animals taken by scientists, camera traps, drones and even tourists," said Tanya Berger-Wolf, director of the Translational Data Analytics Institute at The Ohio State University. "Those images contain a wealth of data that we can extract and analyse to help protect animals and combat extinction."

And a new field called imageomics is taking the use of wildlife images a step further by using AI to extract biological information on animals directly from their photos, said Berger-Wolf, a professor of computer science and engineering, electrical and computer engineering, and evolution, ecology and organismal biology at Ohio State.

She discussed recent advances in using AI to analyse wildlife images and the founding of imageomics in a presentation 20 Feb. at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She spoke at the scientific session "Crowdsourced Science: Volunteers and Machine Learning Protect the Wild for All."

One of the biggest challenges that environmentalists face is the lack of data available on many threatened and endangered species.

"We’re losing biodiversity at an unprecedented rate and we don’t even know how much and what we’re losing," Berger-Wolf said.

Of the more than 142,000 species on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, the status of greater than half are not known because there is not enough data, or their population trend is uncertain.

"If we want to save African elephants from extinction, we have to know how many there are in the world, and where they are, and how fast they’re declining," Berger-Wolf said.

"We don’t have enough GPS collars and satellite tags to monitor all the elephants and answer those questions. But we can use AI techniques such as machine learning to analyse images of elephants to provide much of the information we need." — Phys.org

Continued below…

Wildbook contains more than 2 million ph

Berger-Wolf and her colleagues created a system called Wildbook that uses computer vision algorithms to analyse photos taken by tourists on vacation and researchers in the field to identify not only species of animals, but individuals.

"Our AI algorithms can identify individuals using anything striped, spotted, wrinkled or notched—even the shape of a whale’s fluke or the dorsal fin of a dolphin," she said.

For example, Wildbook contains more than 2 million photos of about 60,000 uniquely identified whales and dolphins from around the world.

"This is now one of the primary sources of information scientists have on killer whales—they are data deficient no longer," she said.

In addition to sharks and whales, there are wildbooks for zebras, turtles, giraffes, African carnivores and other species.

Berger-Wolf and her colleagues have developed an AI agent that searches publicly shared social media posts for relevant species. That means many people’s vacation photos of sharks they saw in the Caribbean, for example, end up being used in Wildbook for science and conservation, she said.

Together with information about when and where images were taken, these photos can aid in conservation by providing population counts, birth and death dynamics, species range, social interactions and interactions with other species, including humans, she said.

This has been very useful, but Berger-Wolf said researchers are looking to move the field forward with imageomics.

"The ability to extract biological information from images is the foundation of imageomics," she explained. "We’re teaching machines to see things in images that humans may have missed or can’t see."

For example, is the pattern of stripes on a zebra similar in some meaningful way to its mother’s pattern and, if so, can that give information about their genetic similarities? How do the skulls of bat species vary with environmental conditions, and what evolutionary adaptation drives that change? These and many other questions may be answered by machine learning analysis of photos.

The National Science Foundation awarded Ohio State $15 million in September to lead the creation of the Imageomics Institute, which will help guide scientists from around the world in this new field. Berger-Wolf is a principal investigator of the institute.

As the use of AI in analysing wildlife images continues to grow, Berger-Wolf said, one key will be to make sure the AI is used equitably and ethically. For one, researchers have to make sure it does no harm. For example, data must be protected so that it cannot be used by poachers to target endangered species.

But it must be more than just that.

"We have to make sure that it is a human-machine partnership in which humans trust the AI. The AI should, by design, be participatory, connecting among the people, among the data and among the geographical locations," she said.

Source: Jeff Grabmeier, (The Ohio State University) via Phys.org

How it works

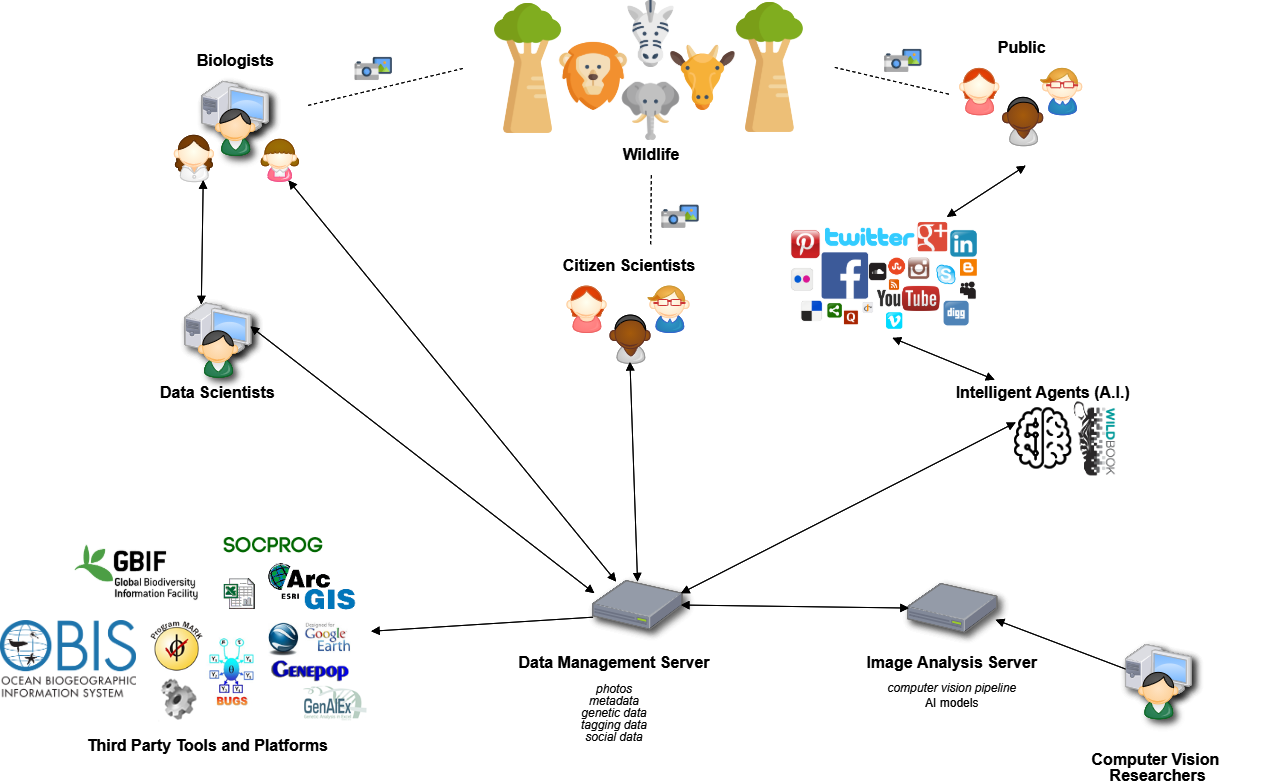

Wildbook blends structured wildlife research with artificial intelligence, citizen science, and computer vision to speed population analysis and develop new insights to help fight extinction. As an open source software framework, Wildbook supports collaborative mark-recapture, molecular ecology, and social ecology studies, especially where citizen science and artificial intelligence can help scale up projects. Wildbook provides a technical foundation (database, APIs, computer vision, etc.) for wildlife research projects to:

- track individual animals in a wildlife population using natural markings , genetic identifiers, or vocalisations

- collect biological samples from a wildlife population and performing genetic and/or chemical analyses (e.g., stable isotope measurements, haplotype determination, etc.)

- engage citizen scientists andor using social media to collect sighting information

- build a collaborative, distributed research network for a migratory and/or global species

- develop a new animal biometrics solution (e.g., pattern matching from photos) for one or more species

- collect behavioral and/or social data for a wildlife study population

The biological and statistical communities already support a number of excellent tools, such as Program MARK,GenAlEx, and SOCPROG for use in analysing wildlife data. Wildbook is a complementary software application that provides:

- scalable and collaborative platform for intelligent wildlife data storage and management, including advanced, consolidated searching

- easy-to-use software suite of functionality that can be extended to meet the needs of wildlife projects, especially where individual identification is used

- APIs to support the easy export of data to cross-disciplinary analysis applications (e.g., GenePop ) and other software (e.g., Google Earth)

- easy data access to animal biometrics and facilitates matching application deployment for multiple species exposure of data in biodiversity databases (e.g., GBIF and OBIS) through a shared platform

Powered by Machine Learning

Because Wildbook allows for easier storage of data and brings together researchers and citizen scientists to create bigger data sets, the issue of curation and data management becomes a more pressing one. Wildbook leverages computer vision machine learning to process images, locating animals, applying species labels, and even suggesting matching individuals from within the database.

This computer vision pipeline works with real-world conditions, allowing for broad contributions. This process gives greater confidence that we know who the animals are and where the have been. Getting this baseline information correct allows researchers to focus on deeper analysis that can bring about actionable change.

Source: Wildbook